Many historians believed that the quality of houses built to meet the needs of the rapidly growing urban population was universally poor, reflecting the stinginess of both builders and landlords. However, these views were overly simplistic, and it was entirely incorrect to assume that all 19th-century cities developed according to the same principles, as if they were a repetition of Coketown—an industrial city of factories and tall chimneys endlessly duplicated. While it is undeniable that many buildings in the city were of poor quality, historians in recent times have argued that the new urban housing of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was not necessarily worse than housing built earlier or even rural housing constructed at the same time. Read more about 19th-century workers’ housing at birmingham-future.com.

Population Growth in the City

It is well-documented that new buildings varied in construction and amenities, both within the same city and across different cities. Skilled workers often lived in better-quality housing than unskilled workers. There was also a clear segregation between working-class housing and the homes of the middle and upper classes.

How does workers’ housing in Birmingham during the Industrial Revolution compare in this context? It is worth noting that, among the major industrial cities of Britain, Birmingham received the least attention in this regard, with fewer historical studies and press publications than other cities.

This was unfair, as Birmingham’s population was growing at an astonishing rate. This growth was not limited to the latter half of the century. In 1700, the population was between 5,000 and 7,000. Over the next 50 years, it at least tripled, if not quadrupled, reaching a record 23,700 people.

While the city’s population had more than tripled in the previous 50 years—far outpacing the national growth rate of around 50%—between 1801 and 1841, it only increased by two and a half times. This was only slightly higher than the national rate and significantly lower than in some other industrial cities. Thus, at the turn of the century, the demand for additional housing was greater than in the following decades.

By the turn of the century, major areas of development were in the north and northwest of Birmingham, particularly around Warstone Lane, Great Hampton Street, and New John Street West. By the 1830s, this area was becoming increasingly densely populated, and by 1838, very little undeveloped land remained in the eastern part of the parish. Interestingly, small allotment gardens, known as guineas and half-guineas, still surrounded the central part of the parish to the west, north, and east.

Two Rooms and a Shared Yard

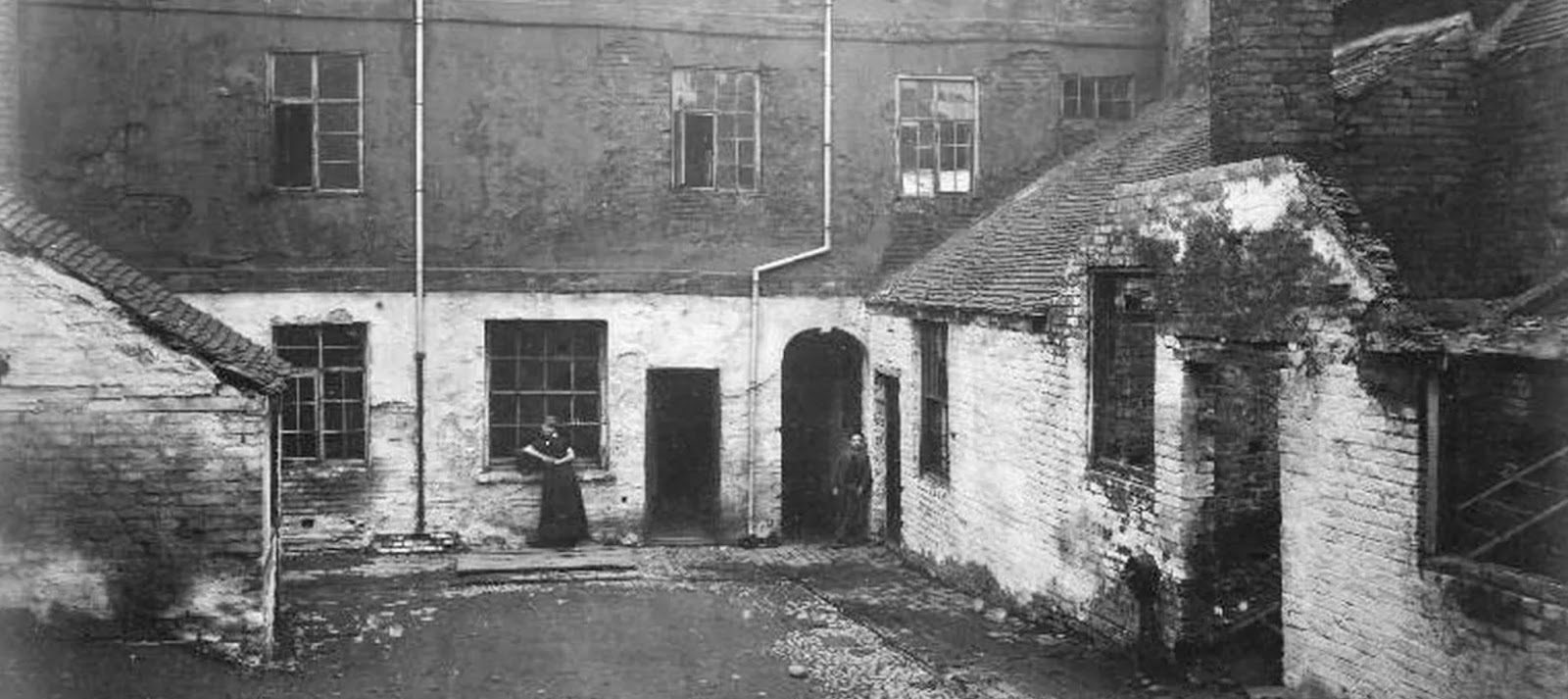

The most common type of workers’ housing built in the latter half of the 18th century in Birmingham consisted of two rooms per floor in two- or three-storey houses arranged around courtyards. These houses were built tightly together and cost between £40 and £60, whereas larger homes built through construction clubs cost between £80 and £150.

Owners of smaller houses came from various professions, including the more affluent working-class families who purchased their homes through construction clubs. Small entrepreneurs were also significant property owners.

For instance, in 1765, two bricklayers—likely employed builders—took out Sun insurance policies for their houses. One, Henry Gough, insured four houses for £220 and another four for £170. His colleague, James Day, insured eleven houses and a school valued between £65 and £15 each.

Many holders of other Sun insurance policies issued that same year were small craftsmen involved in making toys, buttons, buckles, and weapons, as well as carpentry. These policies covered various small properties rented out to others.

It is difficult to determine the exact quality of these workers’ houses built in the latter half of the 18th century. During the war with the American colonies, at least 300 houses were built annually, and after the war ended, this number doubled. Entire streets were constructed in less than two months. In terms of construction scale, Birmingham may have built more houses than any other city in Britain, except London.

Features of Workers’ Buildings

Historians have pointed out that, at the time, there was no regulation over construction methods used by builders. This may explain the architectural problems that persist in the city to this day. One major issue was the narrow courtyards between houses, which limited natural light both in the courtyards and inside the homes.

Some of the houses built so quickly were of poor quality, especially during the war at the end of the 18th century when building material costs, particularly timber, rose sharply. As a result, builders relied on the cheapest available materials. However, not all houses were of poor quality. For example, around 90 houses built on land owned by the Lench Charity Trust were constructed to a higher standard.

Many of these houses sold for at least £100 or were occupied by respectable tenants. Unlike Liverpool or Manchester, Birmingham had no basement dwellings, and its water supply was of high quality. Streets and drainage were generally superior to those in Manchester and other Lancashire cities. All major streets had underground sewage systems, although open drains still existed in Bordesley and Deritend, where many working-class residents lived.

Compared to the slums of Liverpool, Manchester, and London, the poor in Birmingham lived under relatively better conditions. While the older parts of the city had a few enclosed courtyards with poor ventilation, the newer parts of Birmingham had almost none. There were also many tightly packed houses, but they were not always inferior to modern housing in terms of living conditions.

“The City of a Thousand Trades” and Its Housing

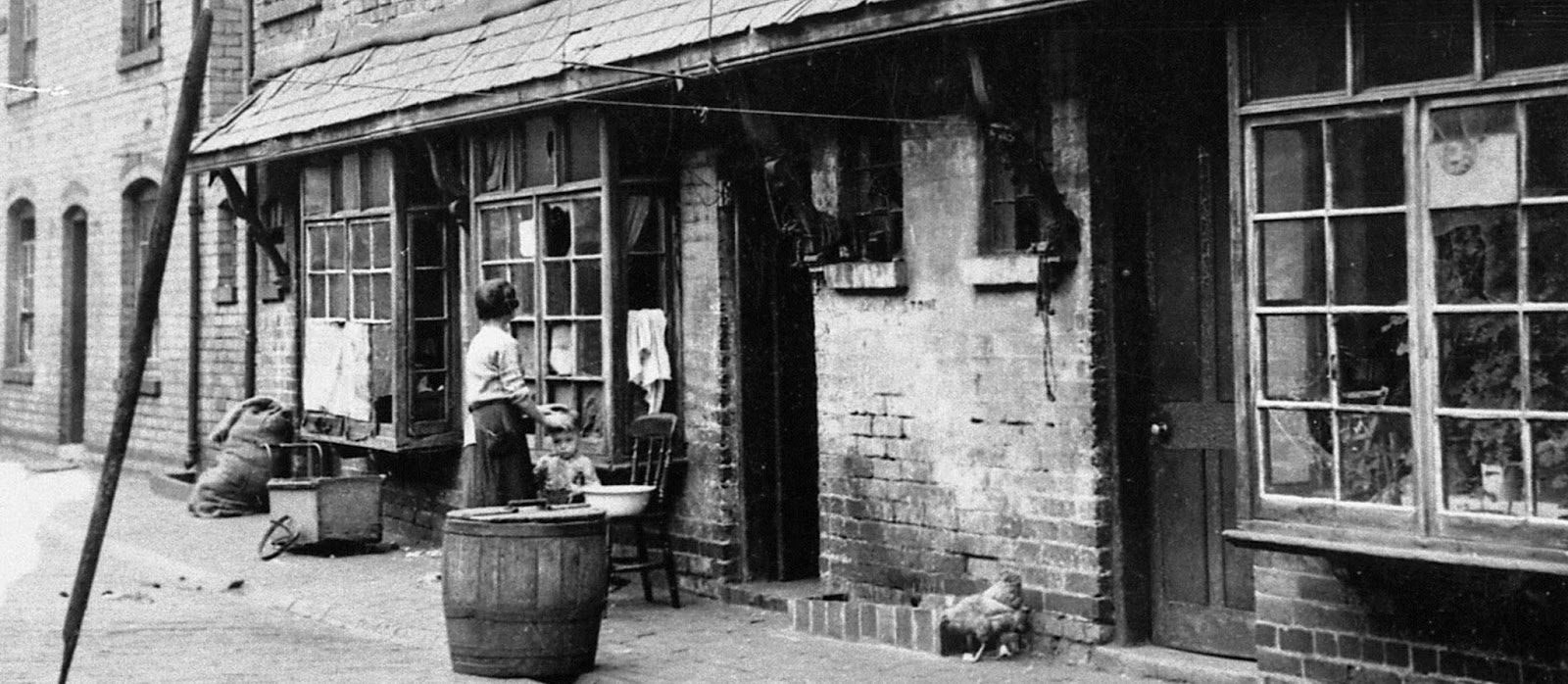

Thousands of homes were built in Birmingham, where working-class families crowded together, trying to make ends meet. These houses, constructed mostly between 1802 and 1831, accommodated the rapidly growing population.

By the early 1800s, Birmingham was not only known as “the city of a thousand trades” but was also the main centre of the country’s Industrial Revolution. The workers of this industrial hub had to live in these conditions. Many who grew up there joked that as children, they thought the city had no grand streets at all.

While those who lived in these homes testified to the harshness of life—where children sometimes slept five to a bed, and shared toilets were common—many former residents believed their time there enriched their lives.