The Classical Revival left an indelible mark on Birmingham during the 1820s and 1830s. Concentrated largely between Ann Street (now Colmore Row) and the upper end of New Street, this area was previously undeveloped but became the site of some of the city’s most iconic structures. Prominent examples include Thomas Rickman’s Exhibition Hall for the Society of Artists, featuring a Corinthian portico that juts over the pavement on New Street, completed in 1829. Another defining masterpiece of this era is Birmingham Town Hall, construction of which began in the 1830s. Next on birmingham-future.com.

What Makes Birmingham’s Architecture Unique

Exploring Birmingham’s architectural landscape offers a journey through a captivating contrast of styles. The city is a blend of timeless classical structures and innovative designs that push boundaries. Walking through its streets, one might ponder the choices of architects—whether driven by the allure of sustainability, tradition, or a harmonious combination of both.

Birmingham’s skyline showcases an eclectic mix of historic and modern influences. Its industrial heritage is evident in repurposed factories and warehouses, which now stand as monuments to its industrious past. Victorian craftsmanship reveals itself in intricate designs, while neogothic spires and arches add drama to the cityscape. The Arts and Crafts movement introduces a human touch with its emphasis on detail and natural materials, while Georgian and Edwardian styles highlight symmetry and elegance.

The post-war modernist wave brought simplicity and functionality to the city’s architectural narrative. Together, these styles weave a rich tapestry that defines Birmingham’s charm and evolution.

The History of Birmingham Town Hall

In 1830, a site at the intersection of Congreve and Paradise Streets was selected for Birmingham Town Hall, a venue also intended for artistic and musical performances. A competition for its design attracted prominent architects, including Charles Barry and Thomas Rickman. However, the project was awarded to the young architect J.A. Hansom, who collaborated with his partner E. Welch. Inspired by classical Roman temples, such as the Temple of Castor and Pollux in Rome, their design marked a significant revival of Roman architecture.

Construction challenges soon arose, as the contractors had underestimated costs, leading to bankruptcy by 1834. Charles Edge was appointed to oversee the project, yet financial difficulties delayed its completion until 1849.

The Town Hall’s interior underwent modifications to accommodate a monumental organ, installed in 1834 by William Hill & Sons. Boasting 6,000 pipes, it was one of the largest and most advanced organs of its time.

Externally, the building was designed as a free-standing Corinthian temple with 14 bays along its longer side and eight bays on its shorter side. Despite its horizontal design not being fully reflected in the interior, the Town Hall became a source of civic pride. It hosted premieres of musical masterpieces, such as Mendelssohn’s Elijah and Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius.

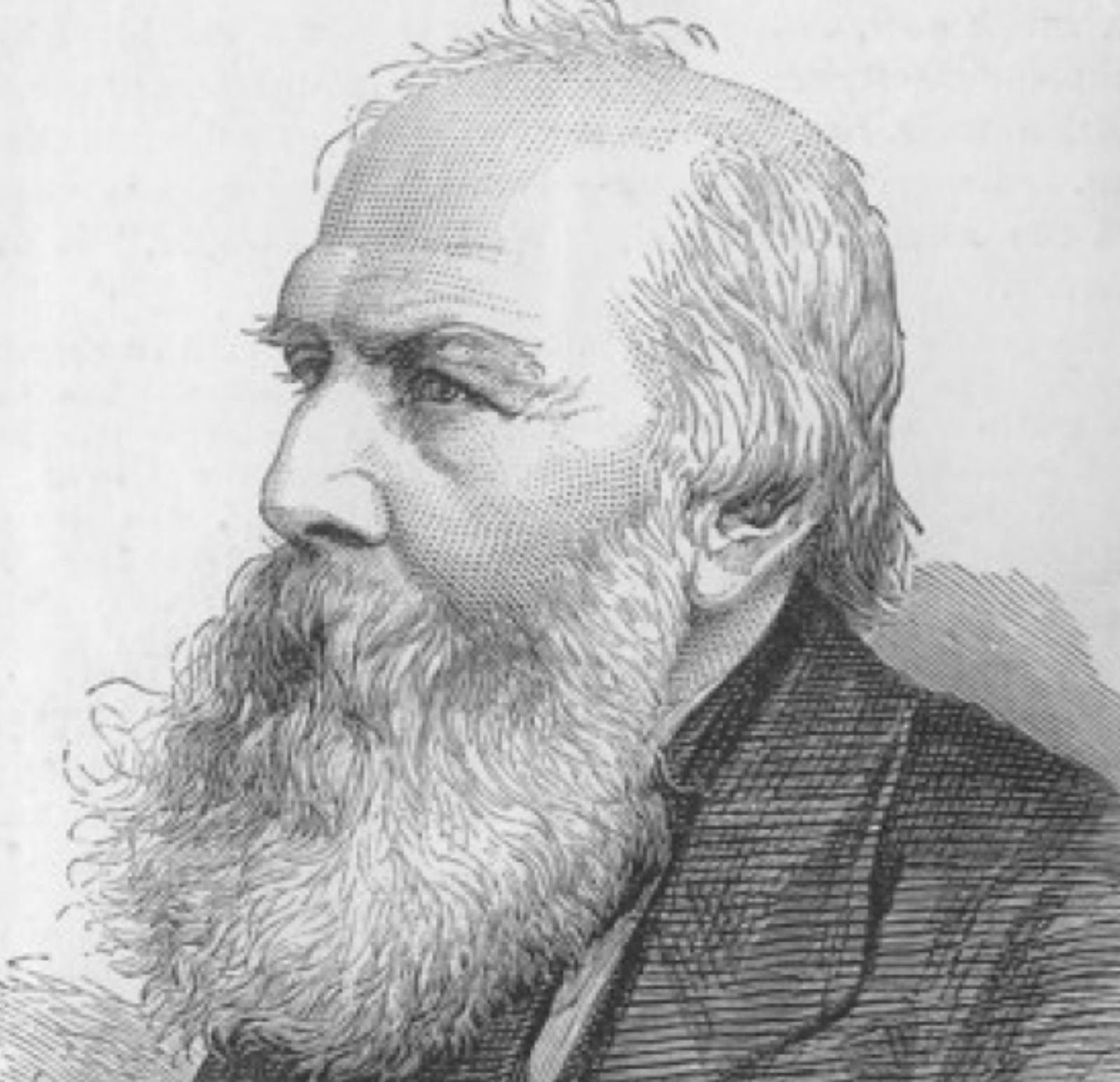

The Architect Behind the Town Hall

Joseph Hansom, born in York in 1803, was renowned for his neo-Gothic architectural designs. He created numerous significant buildings, including schools and churches for Roman Catholics, which can still be found across the UK, South America, and Australia. Hansom also invented the Hansom cab in 1834 and founded The Builder architectural journal in 1843.

After training as a carpenter under his father, Hansom transitioned to architecture, apprenticing with Matthew Phillips in York. In 1825, he partnered with John and Edward Welch, and together, they designed Birmingham Town Hall, a project that marked the beginning of his illustrious career.

Birmingham’s Last Monumental Classical Buildings

Among the few surviving Classical Revival structures in Birmingham is the Birmingham Banking Company, built in 1830 at the corner of Waterloo Street and Bennetts Hill.

The former station at Curzon Street, now a freight warehouse, also stands as a testament to this era. Designed by Philip Hardwick, the architect behind London’s Euston Arch, the station opened in 1842. Its central block featured a grand façade with four Ionic columns, flanked by arches leading to the platform.

An industrial marvel from this period is the former Elkington electroplating factory on Newhall Street, now part of the Museum of Science and Industry. The building’s intricate stucco façade, classical porch, elegant staircase, and spacious halls showcase the Classical Revival’s grandeur.

Birmingham’s architectural diversity is a testament to its rich history and evolving identity. Among its many styles, the Classical Revival era stands out for its elegance and lasting impact, offering some of the city’s most treasured landmarks that continue to inspire admiration today.